It’s a surprise that Davenports has managed to make it on to the Harry Potter tourist trail given the shop is so damned hard to find. You could walk around the dank subways that link Charing Cross and Trafalgar Square for years without stumbling across it, and then one day you’ll turn a corner and whamkazaam, there it is, right in front of you, looking like it’s appeared out of thin air. Well, what do you expect from a magic shop?

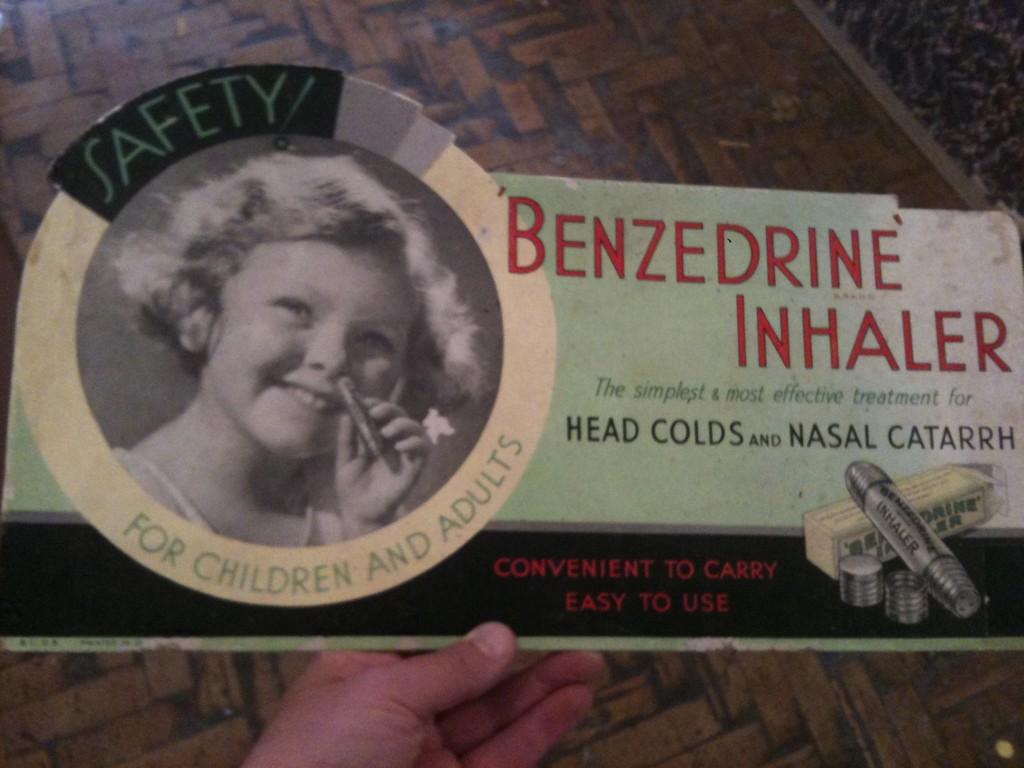

Davenports isn’t any old magic shop (if there even is such a thing), it’s the oldest family magic shop in the world, owned and run by a Davenport for four generations and eyeing up a fifth. It began in the East End in 1898 and its heyday was probably the 1950s and 1960s, when it was based first on New Oxford Street and then Great Russell Street opposite the British Museum. The shop, staffed by magicians only too happy to demonstrate their art, became such a draw for tourists they decided to take themselves off the beaten track and into the tunnels around Trafalgar Square. In the move, Davenports took with them much of the stock, some of the fixtures and all of the atmosphere – walk inside and you step back in time, to late Victorian London, when Davenports was founded and magic was experiencing its first golden age, moving from games of find-the-lady on shadowy street corners into the glamorous Music Hall theatres that dominated popular entertainment.

The vast front window is the first sign that you’ve stumbled upon a refugee from the past. It is crowded with wands, juggling balls, posters advertising old magic shows, ventriloquist dummies, ropes, boxes, cards, red Indian headdresses and a giant dog bone. Enticing no? Opening the door triggers a satisfyingly meaty ‘dong’ from a hidden bell and reveals a small red-hued, slightly creepy interior. Most of the stock, old and weird, is kept in wall-mounted cabinets behind glass doors. The wooden shelves behind the counter are covered with fading handwritten signs – ‘Whoopee Cushion, £1’ –in front of which a young clerk demonstrates sleight-of-hand tricks, pausing only to sell invisible thread and a pack of cards. He pauses between tricks, and I jump in to ask if there is anybody I can talk to about the shop’s history. He disappears, not in a puff of smoke, but round the back, and re-emerges with a neat old lady, wearing a clerk’s apron. This is Betty Davenport, granddaughter of founder Lewis Davenport. ‘I started working here in 1948,’ she tells me, ‘when I was 14 and green as grass.’ Betty has run the business since 1960 and still comes in every afternoon to keep an eye on things. She intends to keep it in the family. One son, Bill, already helps run the business while another, Reg, is a performer, and there are three grandchildren being groomed to take over. Betty has high hopes for the youngest, now seven and doing tricks since he was five. ‘Young boys are inclined to be interested in magic anyway,’ she says, ‘it’s just that when they get older, other things can get in the way.’

Unarguable, and with that thought, conversation peters out. I go back to watching the clerk perform, his brow furrowed in concentration, desperate to get things right and show that in his case those mysterious ‘other things’ were firmly pushed to one side. Davenports has a curiously sober air for a room that’s full of rubber chickens and itching powder. This is a place for serious wizardry, where illusion is business. It’s more like a library than a joke shop. Another customer walks in and starts talking about the art, and I can sense my presence as a non-magician has been noticed. Is it just me, or is there a fear in the room I might hear something I shouldn’t, a trick, as it were, of the trade? So I bid farewell to Betty, close the door and retrace my steps back through the underground passages of Charing Cross, wondering all the while whether Davenports will even be there when I return.