When I started working at Time Out in 1998, I was young but by no means a greenhorn having already done five years at the Sunday Times, where I encountered formidable figures such as Hugh McIlvenny, Steve Jones, Nick Pitt and Chris Lightbown, my own personal mentor. But the journalists at a Time Out where a different breed. They were all very smart, incredibly knowledgeable about their particular field and not shy of letting you know it.

One of the most prominent was Paul Burston, whose desk was just across the aisle from the sports section where I first worked as holiday cover for editor Andrew Shields. For a start, Paul was physically striking. Not quite a gym bunny but certainly more muscular and compact than any of the other scrawny hacks at Time Out who looked as if they barely saw daylight and subsisted entirely on a diet of cigarettes and cheap spirits. Paul spoke in a loud voice with a soft Welsh accent. He would get to his desk some time before midday, and immediately start fielding a seemingly endless torrent of phone calls, exchanging gossip, rumours, ideas and anecdotes with a string of friends.

These conversations were peppered with language that I’d never previously heard outside the playground – queer, dyke, poof. I didn’t know where to look. I soon worked out that Paul edited the Gay section and had been at Time Out for a while, forging a relationship as a journalist who was outspoken against homophobia and fought for gay rights but could be very critical of gay politics and lifestyle if he felt it necessary. I’d never really encountered such an outspoken and confident out gay man before – there were very few gay journalist at the Sunday Times and none, openly at least, in the sports department – nor was I particularly familiar with the gay world of London, despite having gone to Popstarz a few times.

One of my strongest memories of Paul was his sheer fury on the evening of the Admiral Duncan bombing, as he took phone calls about the unfolding horror before going into Soho to see what was going on.

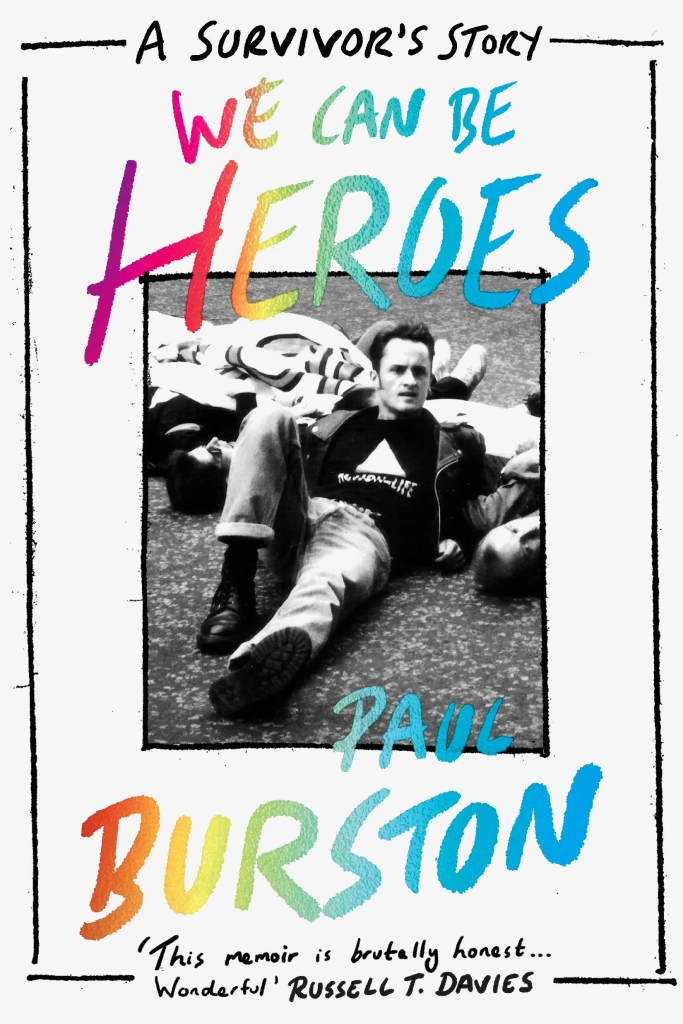

We remained colleagues until I left Time Out in 2010, but I only really got an inkling of Paul’s background when I read an account of his life as an AIDS campaigner that he wrote in Time Out‘s 40th anniversary book, London Calling, in 2008. Now Paul has brought out a memoir – We Can Be Heroes – which covers his life in more detail, which includes striking reminiscences of gay life in London in the 1980s, partying hard while campaigning under the constant shade of AIDS and homophobia. It’s a great book that I recommend heartily for anybody interested in London subcultures and activist politics.

As I read We Can Be Heroes, I realised that while Paul was experiencing the trauma of seeing his friends die of AIDS I was still at secondary school laughing at jokes about the disease. On Facebook, my school’s old boy page was recently hijacked by a number of men recounting the frankly horrific physical abuse they endured at the hands of staff, including pupils from my own time at school who were caned, slapped, strangled and thrown against walls by out-of-control teachers.

I was never physically attacked by teachers but verbal abuse was common. Chief among this was homophobia. There was not a single out gay boy in our school of 800 – because how could any child admit to being gay during the era of Clause 28, when rugby teachers would call anybody who disliked physical violence “a Mary-Anne” and RE teachers told us that homosexuals would go to hell. As a result, in the playground gay insults were the major currency – poof, queer, bum bandit, bender and jokes about AIDS. It’s hard to imagine how this could have been endured by any of the gay boys in the school.

It came as a little surprise when my old school was drawn into controversy recently when the current school chaplain – a man who I realised had been in the same year as me at school and therefore exposed to the same environment of endless, normalised and officially sanctioned homophobia – was accused of banning a gay author from giving a talk to pupils. As Paul’s book shows, we’ve come an awful long way, but there’s still a long way to go.