Flitcroft Street is the short street at the east end of Denmark Street. You might know it from its most famous building – the one with the huge door (theatre backdrops were painted here – hence the big door to get them out on to the street).

Flitcroft Street used to be known as Little Denmark Street. Readers of my book, Denmark Street: London’s Street Of Sound, might recall it was the location of Billie’s, a legendary London gay club populated by musicians in the 1930s that was the subject of a homophobic police raid.

Flitcroft Street is now home to Meanwhile, a gallery run by the Farsight Collective. Walk down Denmark Street, turn right and it’s right there. The Farsight Collective have huge plans for this site. The gallery will be on the ground floor. A couple of floors below, almost directly below Regent Sounds at No 4, that will be a cabaret bar – modeled partly on Billie’s. In the floor between there is space for a live music venue that will hold around 300 people. The Farsight Collective have considerable experience running both clubs and galleries in London so they know their stuff.

This is, in my view, the most exciting thing to happen in the West End for decades. It has the potential of confirming Denmark Street as an essential location for live music, particularly if it encourages the Lower Third (once the 12 Bar) and Here to up their game. Other new arrivals for the street – as yet unconfirmed – will add to this experience by filling in other gaps that are currently lacking in the street’s offering.

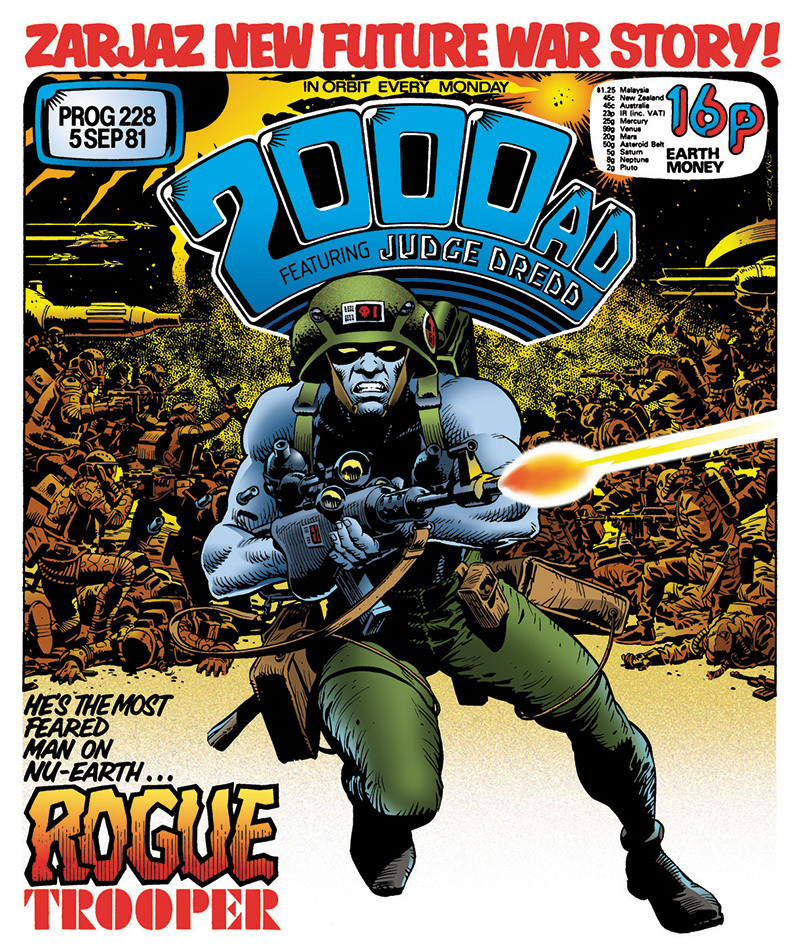

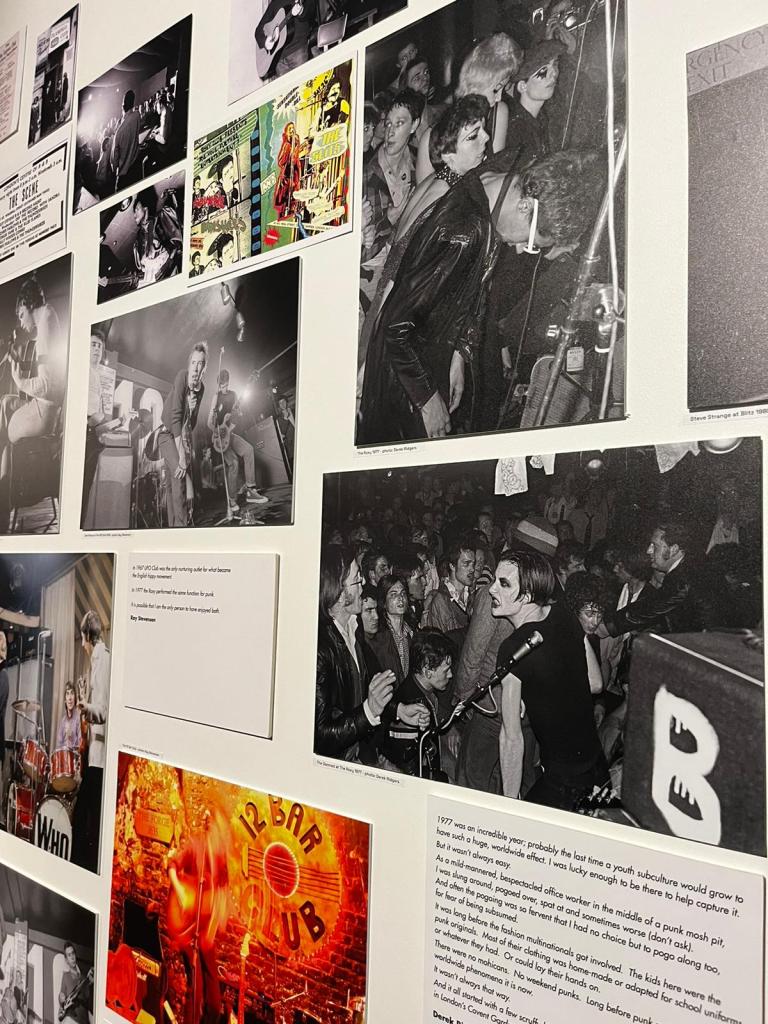

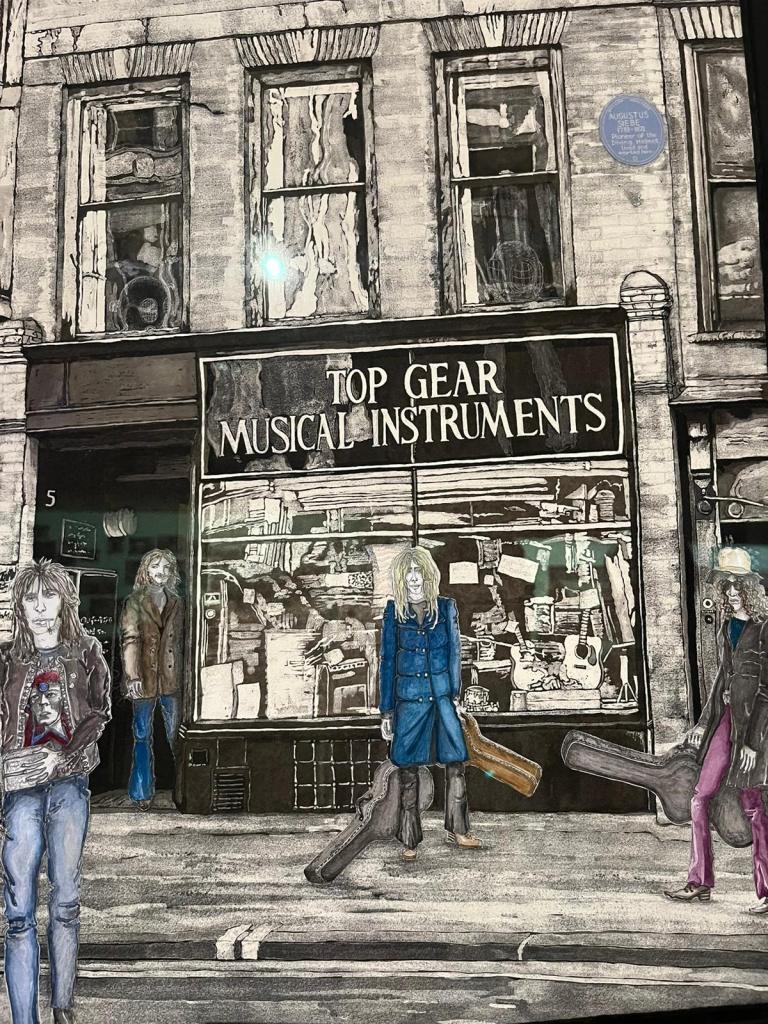

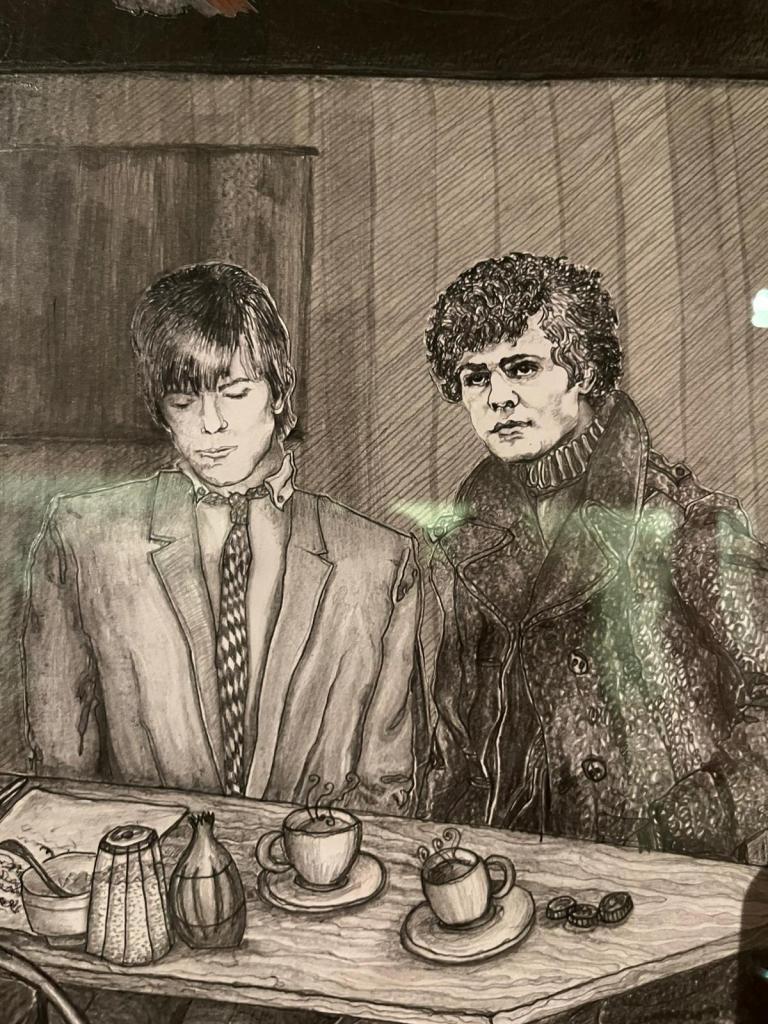

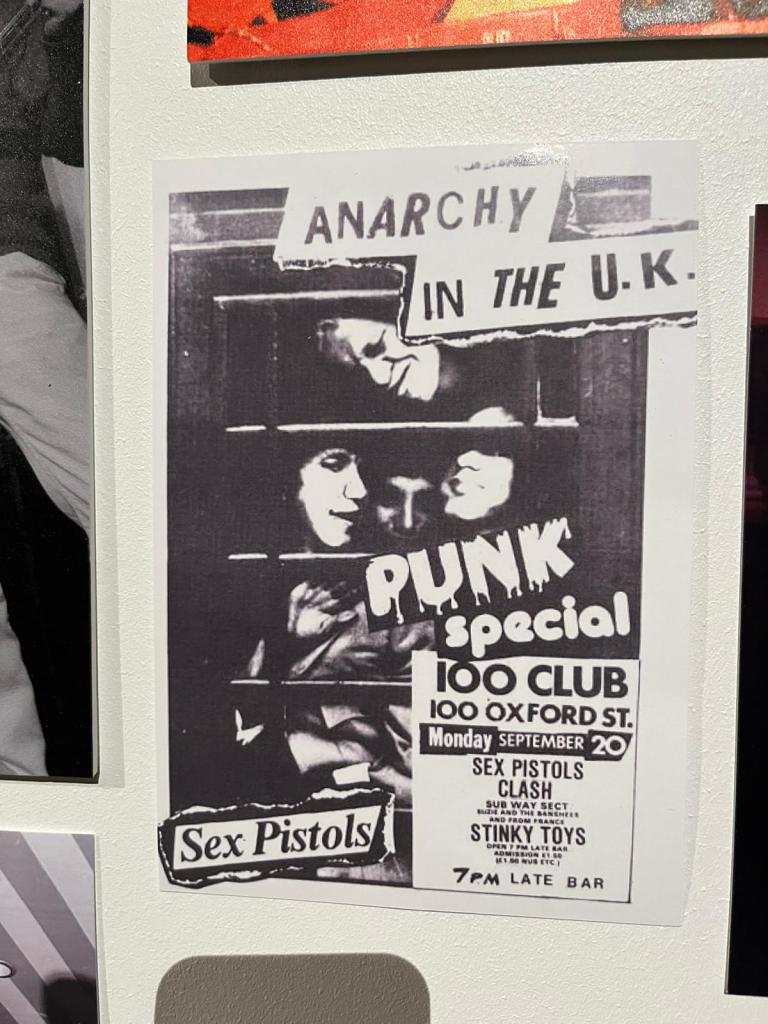

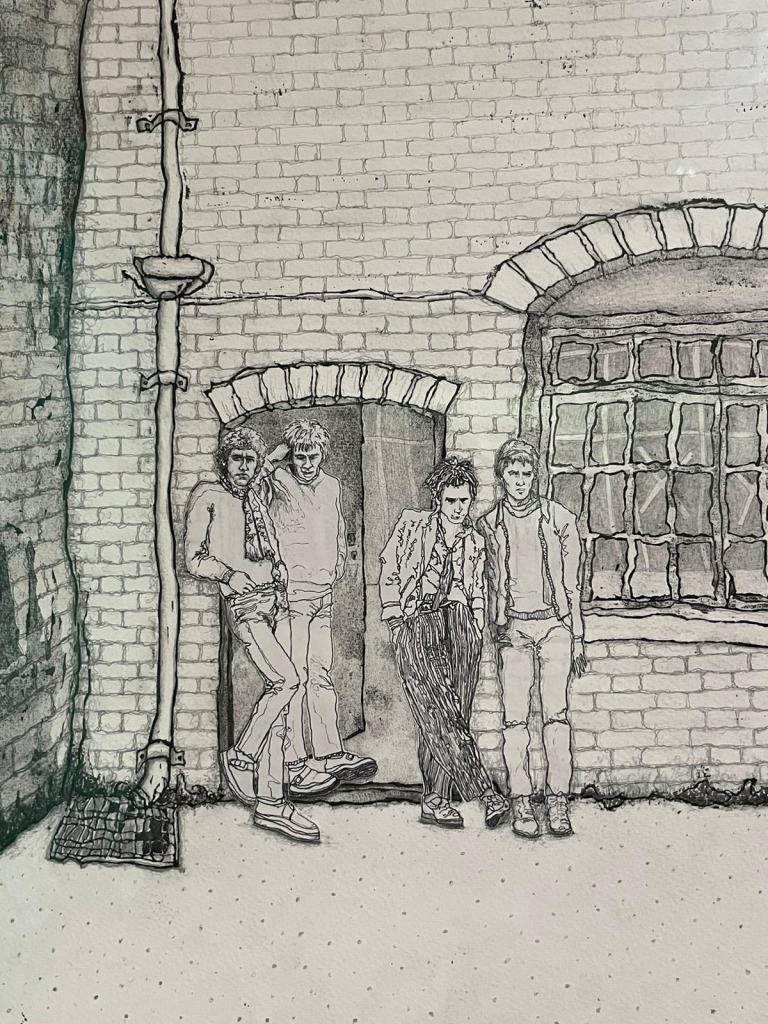

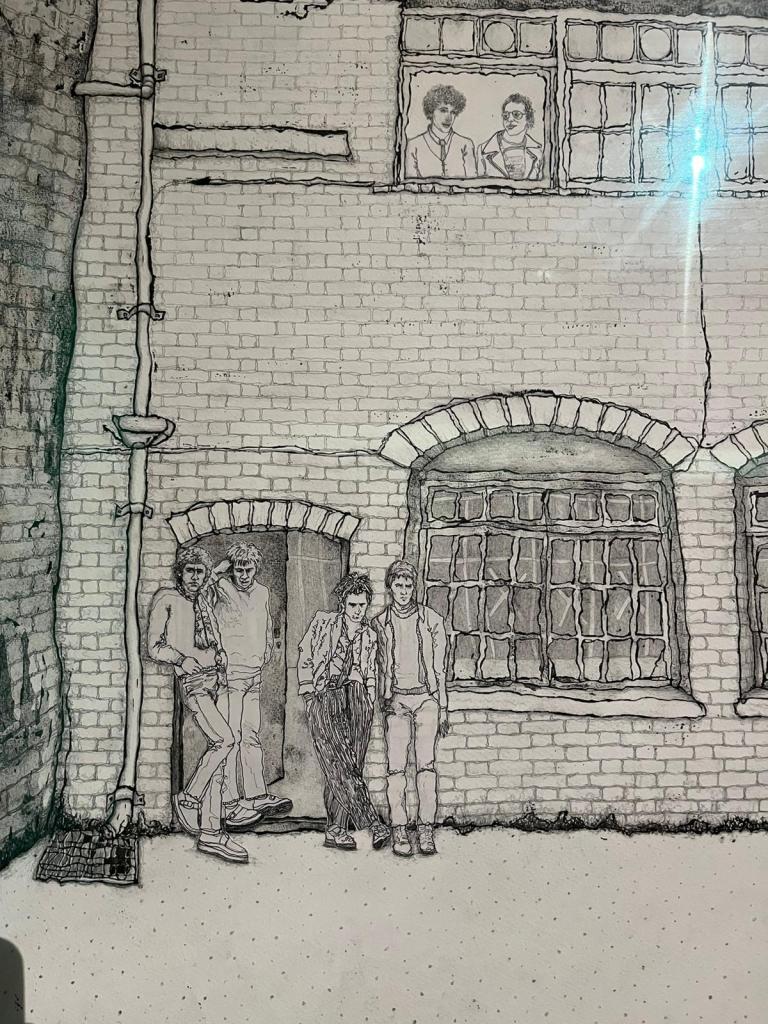

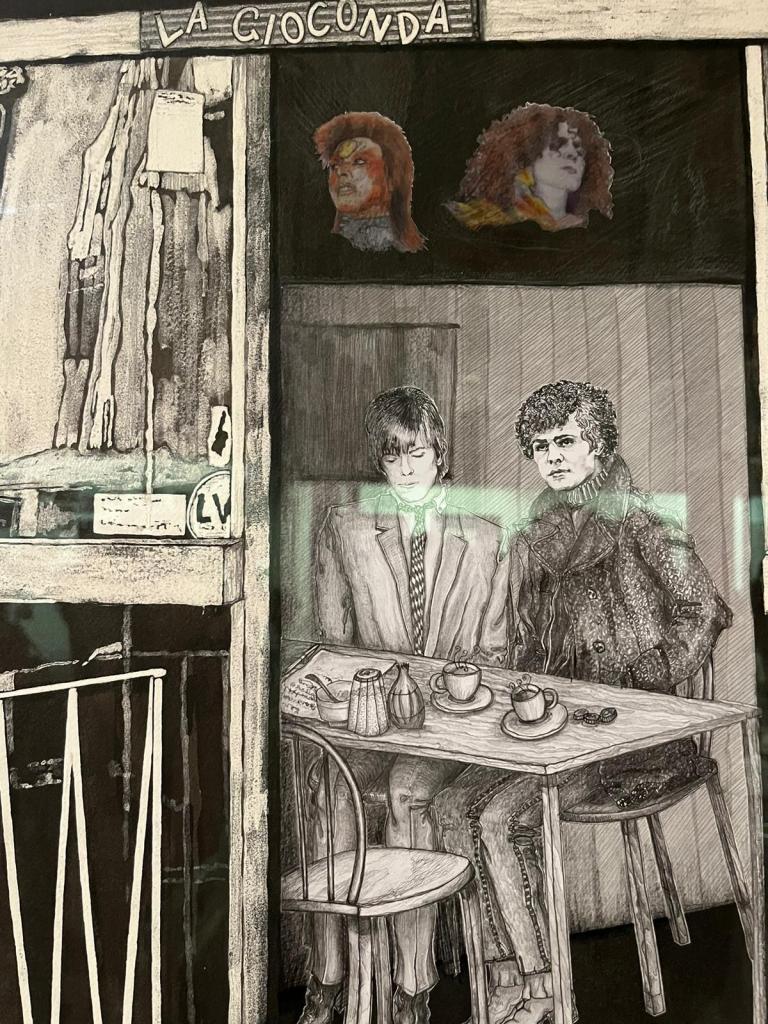

Meanwhile is open weekdays 12-6pm. It is currently hosting an exhibition that celebrates the musical history of Denmark Street and Soho. This includes photographs of great London nightspots from the past, covering everything from jazz to Trash. There’s a video timeline showing London clubs from 1900 to today – apparently there were more nightspots open in Soho during the Blitz than there are today – and some drawings of famous Denmark Street locations including Lawrence Wright House at No 19, Bowie and Bolan at La Gioconda and The Sex Pistols outside their outhouse at No 6.

There is also a short history of every building on Denmark Street using text taken from Denmark Street: London’s Street of Sound.

Other displays discuss the plans for the location and how you can support their license application.

Highly recommended.

Meanwhile, Flitcroft Street, weekdays 12pm-6pm.

![IMG_7092[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_70921.jpg)

![IMG_7094[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_70941.jpg)

![IMG_7095[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_70951.jpg)

![IMG_7091[1] IMG_7091[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_70911.jpg?w=163&resize=163%2C218#038;h=218)

![IMG_7093[1] IMG_7093[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_70931.jpg?w=163&resize=163%2C217#038;h=217)

![IMG_7096[1] IMG_7096[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_70961.jpg?w=329&resize=329%2C439#038;h=439)

![IMG_7098[1] IMG_7098[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_70981.jpg?w=163&resize=163%2C217#038;h=217)

![IMG_7101[1] IMG_7101[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_71011.jpg?w=163&resize=163%2C217#038;h=217)

![IMG_7099[1] IMG_7099[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_70991.jpg?w=162&resize=162%2C217#038;h=217)

![IMG_7100[1] IMG_7100[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_71001.jpg?w=246&resize=246%2C328#038;h=328)

![IMG_7102[1] IMG_7102[1]](https://greatwenlondon.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/img_71021.jpg?w=246&resize=246%2C328#038;h=328)