This is an edited version of a talk I gave last year for the London Fortean Society about London’s shrines. I decided to repost it after visiting the David Bowie shrine in Brixton last week.

To prepare for this speech and in an attempt to get my head around what a shrine was, I began thinking about the simplest shrines you see in London – that’s usually flowers tied to a lamppost after a sudden often violent death or the ghost bikes you see tied to lampposts after crashes.

That got me thinking about the largest shrine I’ve seen in London. This was in those strange weeks after Diana’s death. I was in my 20s and strongly Republican and so had little interest in the public mourning, but an older friend suggested we go and see what was taking place at Kensington Palace as it was something that only happens once in a lifetime. As we walked across Hyde Park this strange smell began to creep across the park – and I can still smell it to this day, the acid sweet stench of rotting flowers. It was indeed an incredible sight. The area in front of Kensington Palace was carpeted with flowers, thousands of bouquets, already turning to compost in the summer heat. People were walking among them, stooping like peasant farmers or bomb disposal experts to read a label. I’d never seen or smelled anything like it. You could not get near the palace gates.

Just look.

What fascinated me also about all this was that it had a seditious, outlaw aspect. There was a lot of noise in the press about whether the Queen was treating Diana’s death with sufficient respect, and this huge impromptu shrine – by the people, against the establishment – was given the atmosphere of an almost revolutionary act. It was a fascinating combination – the privacy of remembrance, carried out on a larger scale with political implications.

So perhaps these are some of the key elements for a memorable shrine: they need to be in memory of a colourful life cut short, possibly violently and unexpectedly, but also be plebeian or proletariat in nature, carrying a sort of unofficial, rebellious, streak, upsetting the forces of the order and establishment.

Unsurprisingly. London is filled with them.

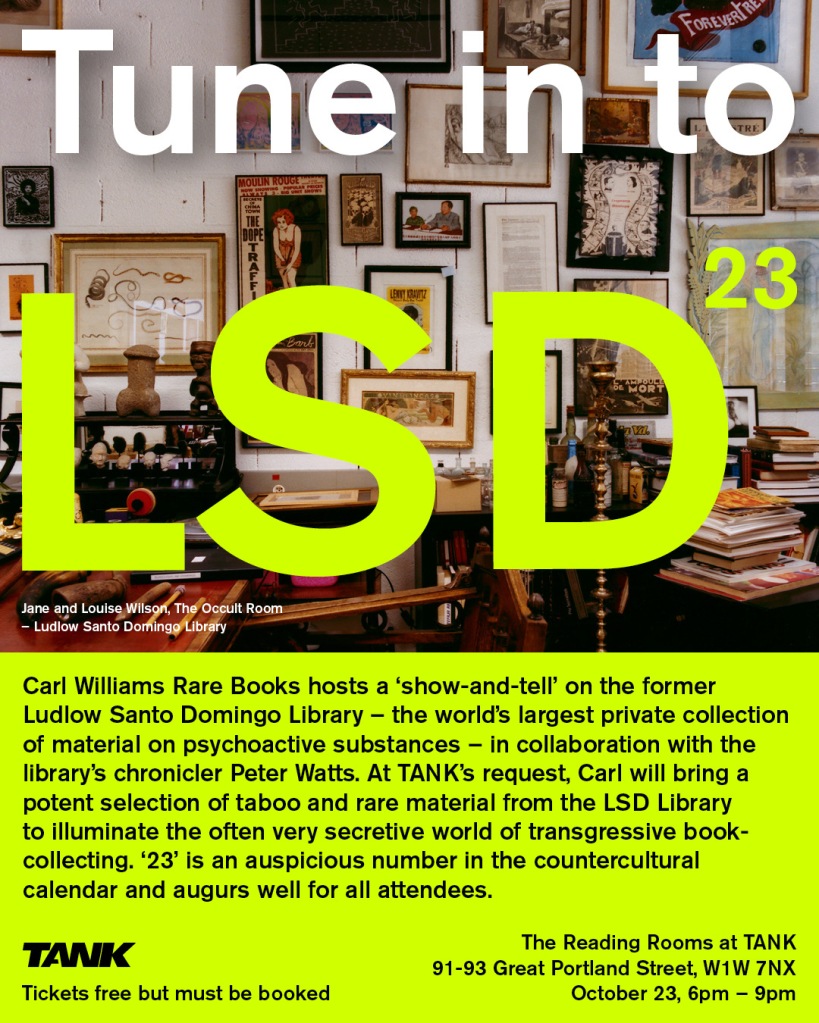

A disarming proportion are devoted to rock stars. This is Freddy Mercury’s old front door in West Kensington, featuring primitive scratched messages from fans all over the world.

There’s also a more or less permanent shrine outside Amy Winehouse’s house in Camden Square. It’s interesting to speculate why some musicians get this treatment and others don’t. For instance, why has Abbey Road become a shrine for Beatles fans but there’s nowhere similar for the Rolling Stones? Perhaps a shrine needs a magnetic location, and the Stones have never created that particular relationship with any single space in the city, perhaps we will need Mick or Keith to die before we find out.

I used to live near Abbey Road, and they had to repaint the wall every two weeks or so such was the flood of graffiti, even though you’d never actually catch anybody in the act of doing it.

Similarly, I’ve always been slightly puzzled as to why Marc Bolan has attracted a shrine. This is the sycamore tree on Queen’s Drive in Barnes that Bolan’s Mini crashed into in 1977, killing him instantly. People have been leaving notes and flowers ever since, and now there’s a bust. Why Bolan? I like T-Rex but don’t really see him as the sort of shamanic, eternal talent you’d think attracted such a tribute.

Perhaps it’s simply the violent nature of the death that appeals to people. But the way his death tree – his cause of death – is being marked is inescapably macabre. In some ways, it makes me think of the old Bill Hicks line, that the last thing Jesus would want to see if he came back to Earth was another bloody crucifix.

That brings us neatly to the religious aspect of shrines. Even in the secular ones, it’s there under the surface, this primitive, sacred need to mark a spot and remember the dead devotionally. But London also has numerous religious shrines. There are two that particularly interest me. One is on Bayswater Road at Marble Arch, where there’s a small convent for nuns. In the basement is a chapel, with walls covered in ancient relics – skin, bone, bits of fingernails – pulled and plucked from some of the 350 Catholic martyrs who were hanged at Tyburn, the gallows nearby. Behind the altar is a replica of the gallows itself. It’s remarkably medieval and extremely weird, especially when a nice old nun is telling you about their favourite piece of shrivelled skin.

There’s also a really interesting element of the shrine found in the canals of west London. Here you often find coconuts floating in the water, sometimes cut in half and containing candles, sometimes tied with ribbons. I used to live on a narrowboat and would occasionally travel west to Uxbridge – the nearer you got to Southall the more you’d see.

I was told they were placed in the water by London’s Hindus in religious ceremonies, with the canal representing the Ganges. A recent article confirmed this: they are place in the canal as an offering to Maa Ganga who symbolises Mother Earth and also the elixir of life, as water is where all life begins. And why coconuts? A Hindu scholar has explained that “Coconuts are the fruit of the Gods – it’s a pure fruit with remarkable qualities, it takes in salt water and produces sweet fruit and it’s neatly packaged too. Also it’s a symbol of fertility, it reflects the womb, and has human qualities – it has two eyes, a mouth and hair.” It’s fascinating that this symbolism has been transported across hundred of miles and generations.

When I was researching this talk, I began to wonder whether London had any graffiti wall shrines – that’s public spaces that have been adopted by street artists to commemorate specific moments and remember people. I’m sure that these exist, but they are hard to pin down because of the transient nature of the form. London does have lots of murals, huge paintings, often commissioned by the community and with a political angle. There’s the Battle of Cable Street mural in Wapping and the Nuclear Dawn CND mural in Brixton. A lot of these are official, but it was interesting to read about the War Memorial Mural at Stockwell tube. This commemorates various aspects of war, with a section for Violette Szabo, who worked behind German lines in WW2 and lived in south London. More recently, artists decided to include on the memorial an image of Jean Charles De Menezes, who was murdered by the police in 2005. But there were disagreements – people felt he didn’t conform to the spirit of the overall piece. Eventually, he was painted out. But there is a small mosaic and shrine to De Menezes nearby.

Then there’s the really strange shrines. I had no idea until this week that the phone box near St Bart’s hospital had been briefly turned into a shrine to Sherlock Holmes after the TV show had him falling from the hospital roof. I don’t imagine there are that many shrines to fictional characters elsewhere in the world.

London also has a skateboard shrine. If you look over the side of the Jubilee Footbridge, you’ll see dozens of broken skateboards lying on one of those immense concrete feet that anchor the bridge to the Thames. These are boards that have been broken during skating sessions by the nearby skaters on the South Bank in the undercroft, and ceremoniously chucked over the bridge to form this strange graveyard.

Then there’s what for me is the saddest shrine of all, partly because it no longer exists. I used to see this all the time when I walked Farringdon, close to Mount Pleasant sorting office, where there are steps going up the viaduct. High up on the wall of one of these dank stairwells you’d see a dozen or so spoons stuck to the tiles.

I always wondered what this was about – even though I think I also partly knew. One day I asked the collective wisdom of Twitter and somebody told me what I’d always suspected: that these were placed here by heroin users in tribute to their dead comrades, each spoon marking a departed soul.

This summarises the essence of an urban shrine for me – it’s clandestine, it’s seditious, it’s violent, it’s about a form of martyrdom and above all it’s about remembrance. I was extremely sad to see the spoons had been removed when the bridge was recently repainted. It’s like those people, those lives, were erased from the public memory. Even as a shrine, they are not allowed to exist.