It was the draw every older Chelsea fan wanted. The plastic flash of the Champions League may excite shallow newcomers, but a League Cup quarter–final at Leeds is what gets the blood pumping. This is proper football, one of the juiciest rivalries in British football, a celebration of regional differences with mutual bad memories stretching back to the mid-1960s.

That’s about how long Leeds have been singing this little ditty about shooting Chelsea scum.

In the late 1970s, Chelsea fans would reciprocate by asking their Yorkshire foes, ‘Did the Ripper get your mum?’ And they’ll always have this.

The fixture will probably have the sort of ‘toxic’ atmosphere that hysterical commentators love to condemn, but it’s also the very reason people pay to watch football in numbers that dwarf that of any other sport. It’s a game that feels more important than it really is, one steeped in tribalism, history and cultural dislike, offering momentary respite from the sterility that defines the modern football-watching experience. For many fans, this is personal, this is pride.

And Chelsea-Leeds has always been huge. The TV audience for the 1970 FA Cup final replay remains the second largest for any sporting event (after the 1966 World Cup final) and it has the sixth largest TV audience of all time – more than any Champions League or European Cup final involving the self-important Establishment clubs of English football. That’s because Chelsea and Leeds had captured a hold on the national imagination since the mid-60s, when two young, stylish, streetwise sides stormed out of the Second Division within a season of each other.

So much in common but so little alike, Chelsea and Leeds set about each other with a passion in a series of increasingly ill-tempered league and cup encounters. By the time a ferocious 1967 FA Cup semi-final was settled by an awful refereeing decision – a last-minute Leeds equaliser from a rocket-like Lorimer free kick was disallowed because the Chelsea wall had moved too early – the foundations were firmly in place. Chelsea and Leeds, they didn’t get on.

‘Hate. We hated them and they hated us,’ is how Chelsea’s Ian Hutchinson once described it, and footballers are rarely so forthcoming about such things. It was a hatred mired in misconception as much as anything else, an embodiment of all of the north and south’s prejudices about each other. This was Yorkshire v London epitomised.

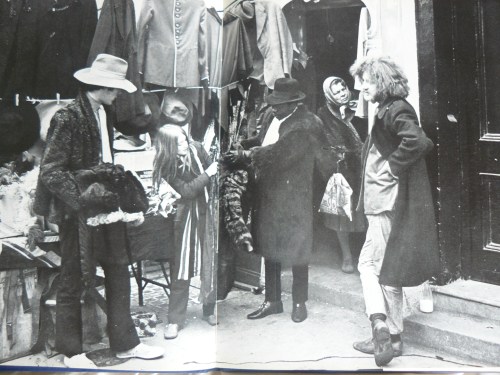

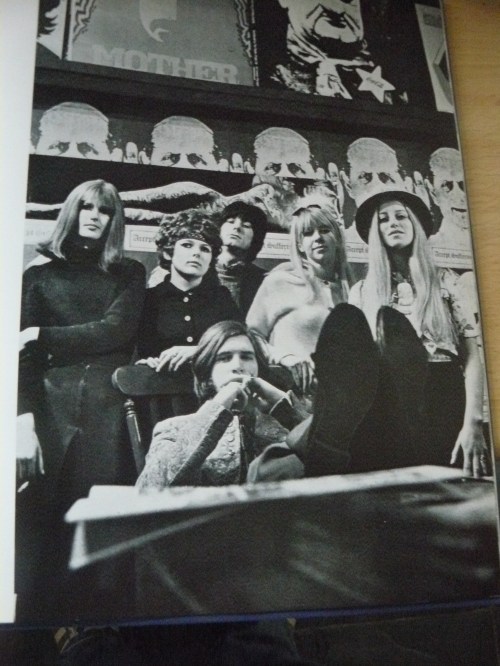

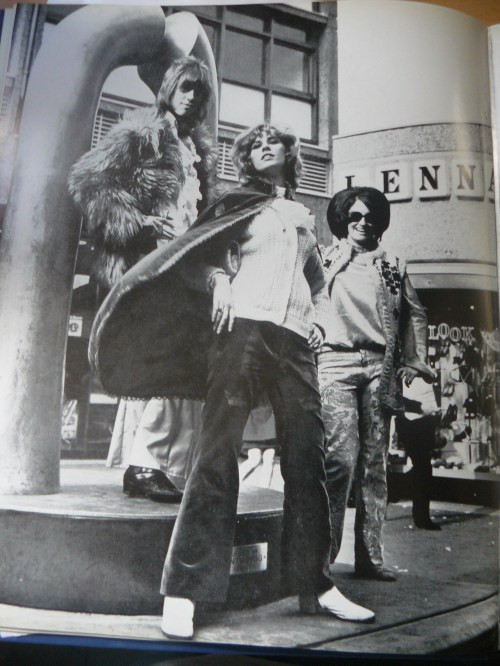

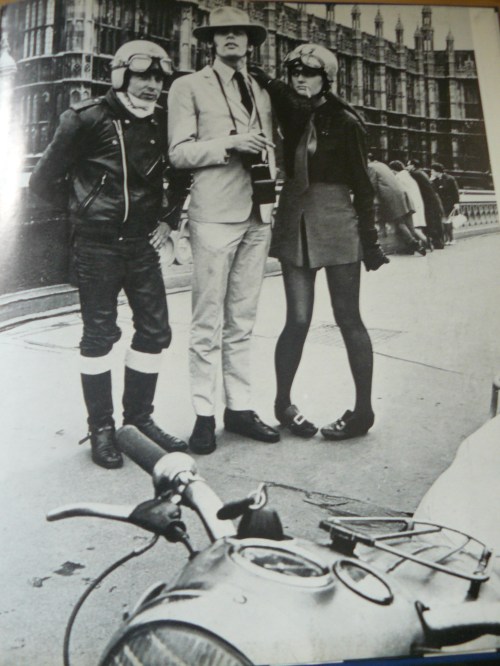

Chelsea considered themselves the club a la mode, King’s Road stylists, swinging London dandies who knew as much about fashion as they did football. On the pitch, they strutted and posed, playing with flair and panache – but only when they could be bothered. Off the pitch, they dressed up, grew their sideburns, hung out with filmstars and were photographed by celebrity photographers with famous fans. No wonder George Best said Chelsea was the only other club he’d ever consider playing for.

Raquel Welch, not in a Leeds shirt

Leeds were more hardworking, more focussed, with a Yorkshire work ethic and attention to detail. They were also masters of professionalism in all its forms. Uncompromising, indomitable, they’d only turn to showboating when the opposition were already on the canvas. To make it worse, neither respected the other’s approach: Leeds thought Chelsea were flash failures; Chelsea thought Leeds were boring and nasty.

These stereotypes weren’t entirely fair – Leeds had beautiful footballers like Gray and Lorimer, Chelsea had roughnecks like Harris and Dempsey, and both teams could be said to have underachieved – but they contained more than a grain of truth. When the teams met at the 1970 FA Cup final, fireworks ensued. It must be the most enthrallingly violent games ever seen in this country. Played today, both teams would count on at least three red cards. This tackle (unpunished) is typical. I’d love to see a You Tube compilation just showing the fouls. Paul Hayward would wet himself.

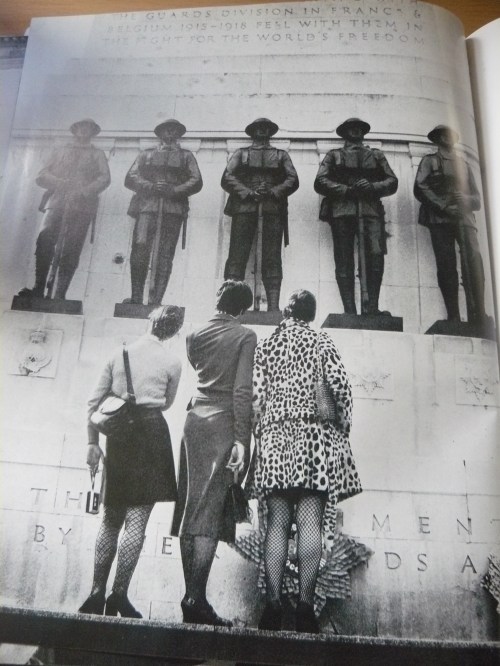

As they rose together, they sank together. From the mid-70s and through much of the 1980s, both clubs endured financial turmoil, relegation, racism and hooliganism. The rivalry remained intense. At a Second Division fixture in 1984, which Chelsea won 5-0 to secure the title, Leeds fans responded by destroying Chelsea’s new scoreboard with a scaffolding pole. This was the scene at another 1980s game at Stamford Bridge, when the fixture still attracted one of the largest crowds of the day.

For a while, things calmed down. When Chelsea won the Second Division title in 1989, the fact they were playing Leeds was almost irrelevant as both sets of supporters maintained an impeccable minute’s silence the week after Hillsborough. When Leeds won the league in 1992, Chelsea fans barely flinched.

The rivalry only really picked up in 1996, when Brian Deane’s vicious ankle-stamp on Mark Hughes signalled the rebirth of Chelsea-Leeds hostilities. For the next few years, Frank Leboeuf, Lee Bowyer, Dennis Wise, Graeme Le Saux, Alan Smith and Jonathan Woodgate produced moments of quite stunning spontaneous cruelty. This was epitomised by George Graham’s side, who arrived at the Bridge in the winter of 1997 with no intention other than to kick Chelsea to pieces. It worked. Leeds had two players sent off before half time, but secured a valuable 0-0 draw. Ruud Gullit’s beautiful but fragile side were never the same.

As Chelsea rebuilt upon experienced foreign lines and David O’Leary went with native youth, the ideology again differed. This time Chelsea came out on top, picking up cups while Leeds imploded (Chelsea even scored, above, one of their greatest ever goals against Leeds). The two sides haven’t faced each other since Leeds were relegated in 2004, in which time Chelsea escaped their own financial reckoning, instead becoming one of the biggest clubs in the world. Leeds, meanwhile, have been scraping along in the lower divisions, the pain exacerbated by the fact they are now owned by much-despised former Chelsea chairman Ken Bates.

So to Elland Road, and while the two clubs have probably never experienced such a vast divergence in fortunes, the fans have been looking forward to this one for weeks. It might be epic, it might be a damp squib, but it will matter, and if we’re really lucky, it’ll be just that little bit toxic.