METROBURBIA: The Anatomy Of Greater London by Paul Knox (Merrell)

London’s suburbia occupies so much space – 695 square miles according to Paul Knox – that it seems ridiculous people even try to summarise it with a single adjective, whether that’s “aspirational” or “banal”. The suburbs contain multitudes and are more like a network of a thousand individual towns then a uniform commuter-ville of identical streets. Knox describes them as “metroburbia”, which he defines as “a multimodal mixture of residential and employment settings, with a fusion of suburban and central-city characteristics”, which is a way of saying that there’s much more to London’s suburbs then large gardens and a fast train to Waterloo: they have shopping centres, office blocks, housing estates, schools, local governments and, critically, millions of residents who never dream of travelling to central London even if they benefit from being within its orbit.

Knox explored central London in his previous book for Merrell, London: Architecture, Building And Social Change, a glossy overview of the relationship between social change and architecture. That book focussed on 27 central districts, looking at how they were originally developed and then exploring in more detail a dozen key buildings. Here he again divides London into sectors, seven of them – Lea Valley, Northeast London, Thames Estuary, South London (all of it), Thames Valley, Northwest London and North London – as defined by the arteries of road, river and rail. Little, though, is made of these sectors once they have been established, with Knox instead taking a chronological overview of metroburbia’s growth and development.

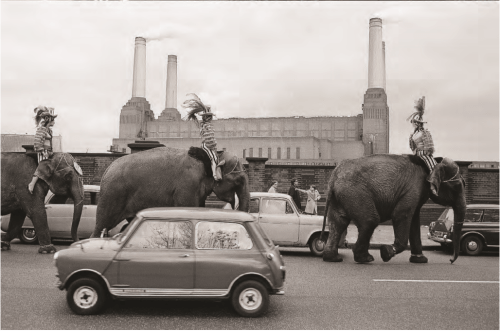

The book is richly illustrated, with the historical narrative interrupted by numerous boxes that focus on individual buildings, trends, regions and housing estates. The story that unfolds is a useful way of understanding how the city has developed. At first, the suburbs were essentially used as a place to put the city’s problems. This is where you could place those big, ugly but necessary things such as cemeteries, asylums, prisons, sewage pumping stations and reservoirs. Housing at this time was just another problem to solve, and in the suburbs there was sufficient space to experiment with both social and private housing, whether in the form of domestic architecture or vast pioneering estates. The increase in population that came with the railways then created a need for further, more localised, infrastructure – libraries, police stations, hospitals, town halls. As a result, one of the joys of this book is the variety of styles it features. There are photos of 60s high-rise towers, modernist mansion blocks, art deco Golden Mile factories, neo-gothic Victorian asylums, Edwardian shopping parades and glitzy suburban villas, with tiny details picked over such as the subtle incorporation of postmodern motifs in domestic housing.

And it’s housing that ultimately dominates the story. The Green Belt is one factor behind this. A crucial reason for the attractiveness of suburbia, it is also a choke on growth with 14 outer boroughs giving more land to the Green Belt than they do to housing. A further complication is the continued fingers-in-ears approach to social housing, something the Government’s recent White Paper on housing suggests isn’t going to change any time soon. Knox picks over all this in a final chapters that analyses the current problem and possible outcomes. What is clear is that the impasse cannot be resolved without direct intervention, and that the fringe land of Metroburbia will be central to any solution.

Buy the book here – http://www.merrellpublishers.com/?9781858946511