The Wellcome Collection is currently showing a typically absorbing exhibition titled Death, but it’s not really about that at all. It features work from a private collection, that of Richard Harris, and largely consists of skulls and skeletons, many of which are actually rather lifelike.

In fact, despite its arresting title, this is in many senses a rather squeamish, clean exhibition. There’s no dying, no decomposition, no pain, little mourning or God. There are no worms eating dead bodies, no cancer destroying live ones. It’s not even particularly morbid. It’s more about one man’s obsession with the human skeleton, stripped of flesh and cleansed of blood, sinew and memory, as portrayed by a number of very beautiful works of art over the centuries. If you want a more gruesome, more real, idea of death, try the Museum of London’s Doctors, Dissection and Medicine Men.

It is tempting to speculate why Harris is so fascinated with his particular idea of death – why so clinical? Why so safe? – but it’s also ultimately rather pointless. In his excellent essay on collecting, Unpacking My Library, Walter Benjamin noted that ‘‘Collectors, like artists, operate out of unconscious motives, and so we cannot be known to ourselves.’ A collection can be about anything, and may reflect a personal interest or a psychological flaw, but the reasons behind their creation are rarely as interesting as you may hope.

What is intriguing about Harris’s love for skulls is that collections are often built as a defence against death itself, a way for the collector to claim mortality for himself in the form of something that will exist after he no longer does so (even if most collections end up being broken by families who lack the passion or obsession to keep them intact). Collections are also about memory, a way for the collector to freeze a moment in time. Every item represents a second, an hour, a week, a month – however long it took to locate and acquire – in the collector’s life that he can look at and recollect for years to come.

A collection is also about surrounding yourself with cool things that you like, although whether this ever makes the serious collector happy is a moot point. In his study of the collecting impulse, To Have And To Hold, Phillip Blom astutely notes that ‘For every collector, the most important object is the next one’, an acknowledgement that the collector will never be satisfied by what they have, as their next acquisition could be the big one, the one that completes the collection, or sends it off in an exciting new direction. This will never happen, of course, locking the collector in a spiral of anticipation and disappointment.

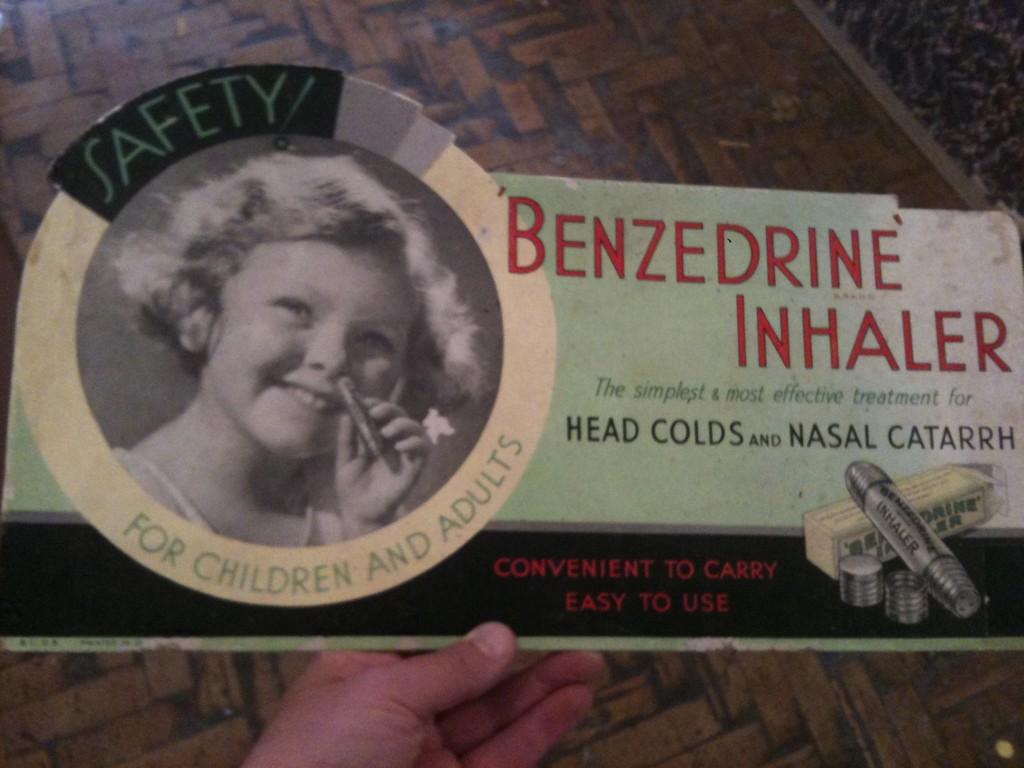

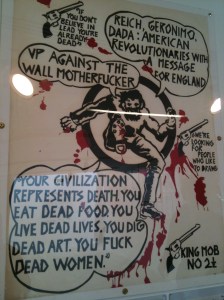

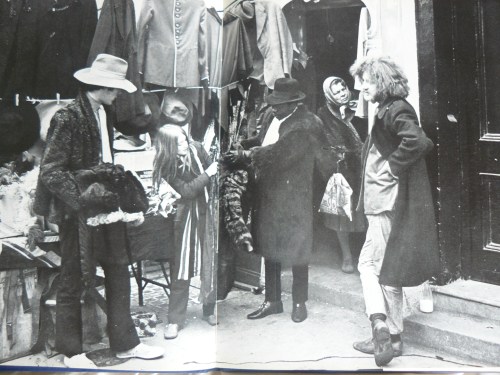

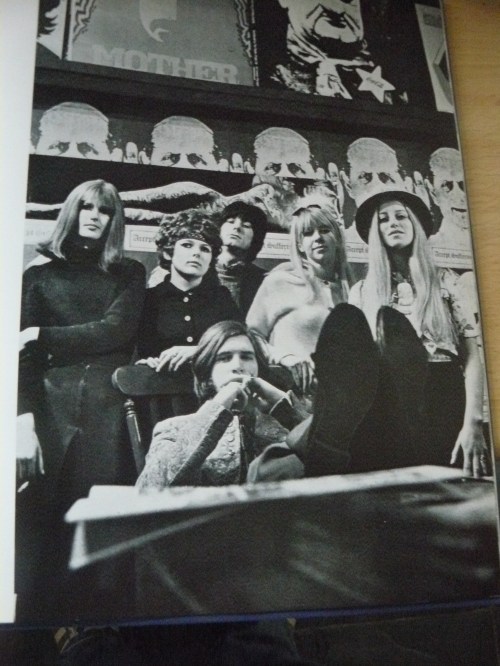

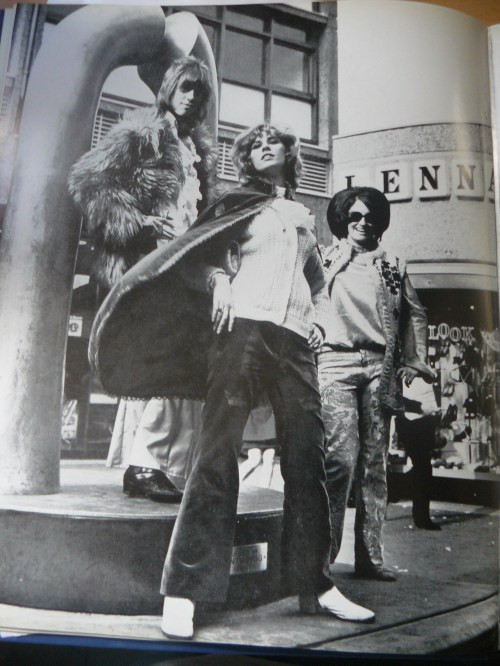

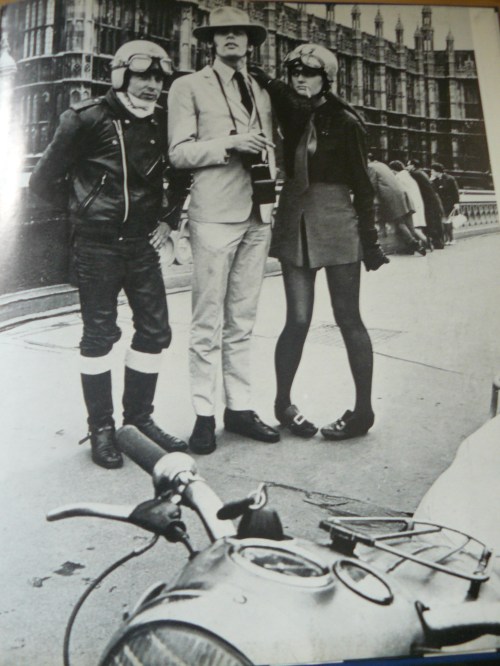

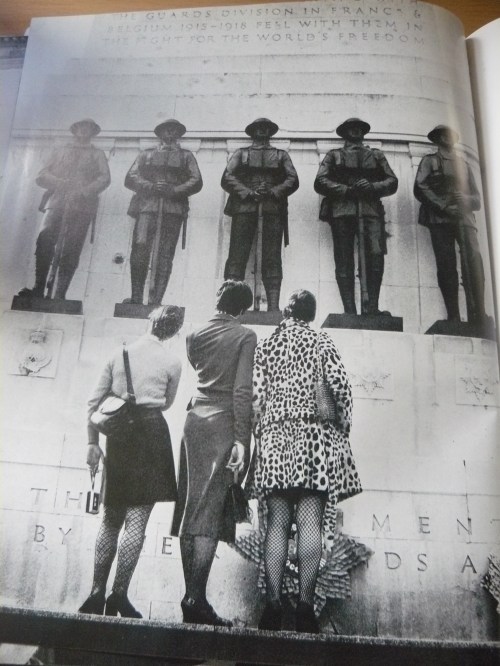

All of this is true whatever is being collected, whether it’s sick bags from aeroplanes, James Bond first editions or things that might be haunted. And just about anything can be collected, if you have the right kind of imagination. My friend Carl Williams, who deals in the counterculture, talks about his idea of collecting around ‘the sullen gaze’, that look of cruel insolence and careless superiority perfected by William Burroughs but which can be traced to many others, putting arresting flesh on Harris’s ambivalent skull.