This piece was published in Time Out in March 2006.

You must have noticed them: jolly green garden sheds that squad in odd spots of London like displaced emerald Tardises, steam coming out the windows and queues of black cabs lining the streets outside. These are London’s few remaining cabmen’s shelters – 13 in all, for 23,000 drivers – places where cabbies can gather to enjoy tea and sympathy away from the hopeful eyes and raised arms of the stranded, late and lazy who make up their regular custom. The Russell Square shelter is the domain of Maureen, 52, who runs a tight ship, keeping an eye on regulars like Ken (‘Say I’m 21’) and Malcolm (‘I’ve been a cabbie for 37 years. That’s all you need to know’).

‘These places are very interesting to the outsider,’ I say, by way of introduction.

‘They’re even more interesting when you’re on the inside,’ Malcolm replies.

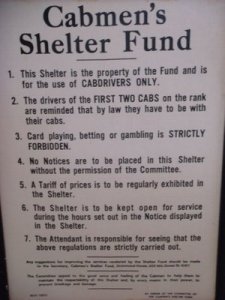

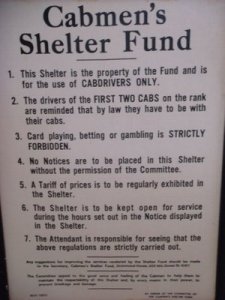

He and Ken come in every day, more or less, to swap tales of fares and roadworks, grumble about Ken Livingstone, talk football, and have something to drink and a bite to eat. They’re keeping alive a long tradition. The Cabman’s Shelter Fund was created by Sir George Armstrong, a newspaper publisher who get fed up waiting for cabs in the rain when drivers had decamped to the nearest pub. He started a fund to supply drivers with a place to get out of the cold and enjoy a cheap meal without straying from the cab stand. The first shelter, erected in 1875, was located on the stand nearest his house (in Oxford). Because the shelters stood on a public highway, the police stipulated they weren’t allowed to be any larger than a horse and cart. At their peak, there were more than 60 in London. Although meant for cabbies, the public could also pop in. Ernest Shackleton was said to frequent the Hyde Park Corner shelter, while the Piccadilly one was nicknamed the ‘Junior Turf Club’ by bright young things, who smuggled in champagne despite the strict teetotal licensing regulations.

Their number declined after WWII as they fell victim to bombs and road-widening schemes, but for a time where a notable feature of London life. HG Wells wrote about ‘the little group of cabmen and loafers that collects around the cabmen’s shelter at Haverstock Hill’, while PG Wodehouse went into greater detail in ‘The Intrusion of Jimmy’ in 1910.

‘Just beyond the gate of Hyde Park… stands a cabmen’s shelter. Conversation and emotion had made Lord Dreever thirsty. He suggested coffee as a suitable conclusion to the night’s revels…. The shelter was nearly full when they opened the door. It was very warm inside. A cabman gets so much fresh air in the exercise of his duties that he is apt to avoid it in private life. The air was heavy with conflicting scents. Fried onions seemed to have the best of the struggle, though plug tobacco competed strongly. A keenly analytical nose might also have detected steak and coffee.’

Food, warmth and companionship are the key. As WJ Gordon wrote in 1893’s The Horse World of London: ‘The cabman is not so much a large drinker as a large eater. At one shelter lately the great feature was boiled rabbit and pickled pork at two o’clock in the morning, and for weeks a small warren of Ostenders was consumed nightly.’

The menu doesn’t stretch to rabbit now, with cabbies preferring tucker that is more in keeping with what a tired cabbie needs, and prices to match. Tea and coffee are 50p. Hot food starts at a quid.

Maureen We do soup, sarnies, fry-ups, curries, jackets… I know what everybody wants. I know everybody who comes in, what he eats and what he don’t eat. Malcolm here had boiled eggs with cucumber in rolls. Except Wednesday. He has baked beans on toast on Wednesday. Ken, he don’t eat nothing. He has a cup of tea.

Time Out You don’t eat here?

Ken No! And I haven’t been in hospital either. Look at the pictures: there’s three up there, four, five, six. All dead. And they used to eat in here.

Malcolm That’s why we’ve got the sign up there: ‘God’s waiting room.’

TO It’s for older cabbies then?

Ken No, anyone can use it. We have one young lad comes in – how old’s Gary, Maur?

Maureen Forty-four. Some of the other shelters are very cliquey – no, I won’t tell you which. If a stranger comes in, they’ll say, ‘You can’t sit there, it’s so-and-so’s seat.’ But we’re not like that.

Malcolm We just check ’em straight out.

Maureen No, we’re friendly here.

TO There’s lots of Arsenal flags, do you have to be an Arsenal fan?

Ken We get a lot of Arsenal, unfortunately.

Malcolm The Tottenham fans get in and out early.

Ken We let the Arsenal in here ‘cos they’re not allowed in the other shelters.

Maureen This one’s been going since 1901. It used to be in Leicester Square, but moved up here.

Ken That was in 1960-something. When I started cabbing in 1967, it was in Leicester Square. I reckon it moved in around 1969.

Malcolm They’re not all the same size.

Maureen They’re similar, but some are longer or wider. They never used to look like this inside though. They used to have seating all round the sides and a big square heater in the middle. People would bring their own food to cook, but there was no kitchen – it was really for keeping warm. Now it’s more like a caravan, with a kitchen at one end and tables at the other.

TO I read they were originally built to keep cabbies out of pubs.

Ken Well, that didn’t work did it?

TO Can non-cabbies come in here?

Ken Builders come in sometimes and have a cup of tea, but if it gets crowded they have it away and let the drivers in.

Malcolm Cabbies get priority.

TO Who owns this one?

Maureen I rent it off the Trust Fund. I pay the rent and the bills out of what I make. It’s all right in the summer, but in winter it gets very cold. Once you start letting people in, it’s okay, and in the summer we have all the doors open or sit outside. We get heat from the ovens as well.

Ken That’s why they have us two come in here before the rest, to warm it up.

TO What are your opening hours?

Ken That’s a sore point.

Malcolm When she wakes up.

Maureen These are the only two who come in at this time, so I open for them.

Ken We’re up early – we go out at 4.30 or 5am. The others don’t start till seven or eight, so they don’t want a cup of tea or a sandwich until about 12 but we get hungry before. I eat elsewhere. I ate here once and was laid up for two years.

TO When do you close?

Maureen About half-five. We get some people sitting here all day.

Malcolm We get a lot of people that put their head round the door looking for cabs or information.

Maureen There’s a bloke from Holland who’s fascinated with black cabs. He comes over now and then to talk. We get people all the time. Who’s that bloke off the radio who talks and talks?

Ken Robert Elms

Maureen Yeah, he’s been in here.

Ken And what’s-his-name, Ricky Gervais, he’s always walking past, says hello. Angela Rippon popped here head in the other day.

Maureen And then there’s that bleeding Madonna. She came in to try and get a cab.

TO Do you get any women cabbies?

Maureen Yeah, we’ve got Marion. But they don’t seem to stay – they have one look and go straight out again. We’ve too many nutters. We’ve Mad Bob, Cockhead, the Village Idiot…

Ken We’re all different in here and we’ve all got our stories.

Malcolm We come in to keep track of who is alive and who is dead.

Maureen You’d be surprised how many we can fit inside. It holds ten or 12 sitting but for Christmas dinner we have 30 or 40 standing inside.

Ken We get slung out, me and Malcolm. It’s better anyway – if anybody’s going to get a turkey with bird flu, it’s Maureen.

Maureen doesn’t rise to the bait. She’s used to it. And, as it has every day for more than 100 years, the hut fills with the smell of fried onions. The cabbies start to file in for lunch, and I have it away to let them grumble, joke and eat in peace.