It’s only because I became a journalist that I spent several hours last year in a dungeon in the London suburbs. I was meeting Mistress Xena, a dominatrix, who was publishing a book that contained dozens of letters she had received from prospective clients during her career. Having carefully read the letters, which veered from the funny to the wince-inducing, I was looking forward to meeting Mistress Xena to learn about her work and see her dungeon.

I was especially fascinated by these letters, which revealed so much about some people’s secret sexual fantasies. Many (most? all?) couples enjoy aspects of S&M in the bedroom without perhaps even recognising it as such, but this was all a long way further down the road, as writers spoke of their desire for ‘total submission’ and offered detailed explanations of the roles they wanted to explore and the violence they wanted done to their bodies. This desire for total physical and verbal humiliation fascinated me and I wanted to understand more about it.

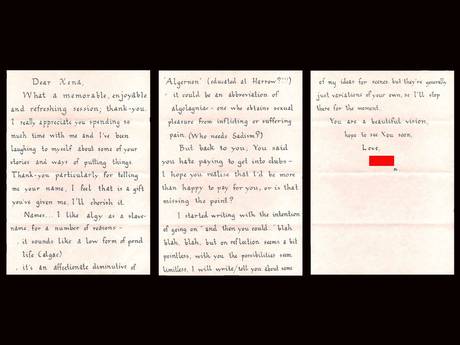

You can get an idea of what I discovered in this extract, which ran in yesterday’s Independent on Sunday. The full story is contained in the book, Submitted: Letters To A Dominatrix, which also contains reproductions of many letters plus related art exploring fetishistic and sado-masochistic themes. Our lengthy interviews form the introduction to the book. It covers a lot of ground, but focuses on what really happens in dungeon, where the dominatrix has to balance what is desired with what is possible. She must filter truth from fantasy while providing something that still ticks the right boxes for the client.

Among the many things we discussed, were the reasons Mistress Xena became a dominatrix having trained as an actor and bouncer. She told me:

As a bouncer, I’d worked at clubs where drugs and alcohol were commonplace. I didn’t enjoy it. The drugs and the industry around them attracted the worst types of people and I couldn’t trust anybody. I spent almost every night waiting to get stabbed, preparing to break up yet another fight or trying to find a man who had groped a young woman, having acted on the mistaken belief he had the right to touch anybody he felt attracted to. After being exposed to this genuinely squalid environment, the fetish clubs came as a surprising relief.

My first fetish club was the Sex Maniacs Ball in London. For many, it would have been intimidating but I realised the club allowed an amazing variety of people to co-exist happily – a woman in her 80s, people in wheelchairs, people of all sizes and every colour and race, gay people, straight people, transgender people. Among the bizarre clothing and behaviour it was clear that people in the scene had great mutual respect for each other. Nobody was taking drugs as stimulants and narcotics interfere with the senses, and women could walk around wearing nothing except a dog collar and a pair of shoes and nobody would touch them without permission. This was incredibly refreshing.

The exhibitionism fascinated me. More people are interested in what happens inside a fetish club than are prepared to admit. People are nosey, people are interested in sex and to watch, to be a voyeur on the fetish scene is perfectly fine, you don’t have to get involved and you certainly won’t get touched. People were enjoying performing in front of an audience, and everybody was wearing costumes – it was like living theatre. One club had a funfair where you saw things you wouldn’t believe, like a man in a gimp suit sitting in a spinning teacup or a dominatrix on the dodgems.

For more, check out the book: Submitted: Letters To A Dominatrix.