This piece is in the current issue of BMI Voyager. The photo of Herne Hill Velodrome is via Adrian Fitch.

It’s unlikely that any of the world’s top cyclists will be thinking about London’s history with the bike when they set off from the Mall for the gruelling 250km Olympic road race on Saturday (July 28th), but if they do pause for thought, they’re starting from the right place. The route will take cyclists through Putney, Richmond and Hampton Court deep into the scenic Surrey countryside of Woking and round Box Hill, but it starts and finishes near Hyde Park, which is where cycling in the UK first really took off.

Cycling had premiered in Battersea Park in the 1880s, but it was in Hyde Park that the great Victorian cycling craze went overground in the 1890s. London was still a horse-happy city at the time, so when 2,000 cyclists – mainly women, dressed demurely with natty bonnets– formed a parade to cycle round the park in the spring of 1896, those on horseback didn’t know quite what to make of it. Bicycles were still a new thing. Penny-Farthings had been around for a while, but were about as common a sight in Victorian London as they are now, and it took the invention of the ‘safety bicycle’ – one with wheels the same size and pneumatic tyres – in the 1880s for that to change. Indeed, such was the enthusiasm with which women took up cycling, that Victorians were torn between trying to find ways to make money out of it, and trying to ensure it was morally appropriate. With typical Victorian ingenuity, they managed to do both – the Chaperon Cyclists’ Association supplied female escorts for solo women cyclists for 3s 6d an hour, while to avoid any dangerous friction you could purchase special ‘hygienic’ bike seats, which had a modest dip in the area where a lady’s genitalia would usually meet the saddle.

Hygienic seat or not, this was, almost without exception, a hobby enjoyed by the upper classes – the Lady Cyclists Association of 1895 was founded by the Countess of Malmesbury – and the Olympic road race aptly passes through some of the poshest areas of London, along the luxury-lined Knightsbridge and down through the smart streets of Chelsea to Putney Bridge. In 1896, the Countess wrote wittily in The Badminton Magazine about the dangers of cycling around these very Belgravia streets thanks to ‘a new sport’ devised by Hansom Cab driver: ‘chasing the lady who rides her bicycle in the streets of the metropolis’ excited by the ‘petticoat which “half conceals, yet half reveals”… I cannot help feeling that cycling in the streets would be nicer, to use a mild expression, if he’d not try to kill me.’

It wasn’t until 1934 that a solution to this perennial problem arrived, when the UK’s first bike lane was opened not far from where the road race course makes its progress through West London. This specialist cycle lane stretched for two-and-a-half miles alongside the Western Avenue and was a belated response to the scarcely believable statistics that recorded 1,324 deaths of cyclists on British roads the previous year. Despite these awful figures, cycling groups opposed the innovation, arguing bikes should not be forced to give up their place on the road to the new-fangled motor car. It’s not an argument they were ever likely to win.

Roads will be close to traffic on July 28, however, and as the Olympic cyclists make their way towards the river, they will pass Kensington Olympia, the huge exhibition hall built in 1883 and used for all manner of spectacular entertainment –promoters would think nothing of flooding the arena to recreate Venice In London, for instance. Anything fashionable was fair game and cycling races were held here during the 1890s. A mixed-tandem race – one male rider and one female – attracted huge crowds in January 1896. Weird events like this were common at the time –the Crystal Palace in Norwood hosted a bicycle polo international in 1901 between Ireland and England (Ireland won 10-5).

After crossing Putney Bridge, the race continues through Putney, where one of London’s many Victorian velodromes was once located, drawing crowds of 10,000. Putney also featured in one of the first cycling novels, The Wheels of Chance, by HG Wells, a writer who always had an eye for a new invention. In it, the hero, Mr Hoopdriver, leaves his dull job in Putney to go on a cycling holiday on the South Coast following a route out of London very similar to the one that will be taken by the Olympic racers. The race later passes through Woking, where Wells lived and set part of War Of The Worlds – Woking has boasted a huge statue of a tripod since 1998.

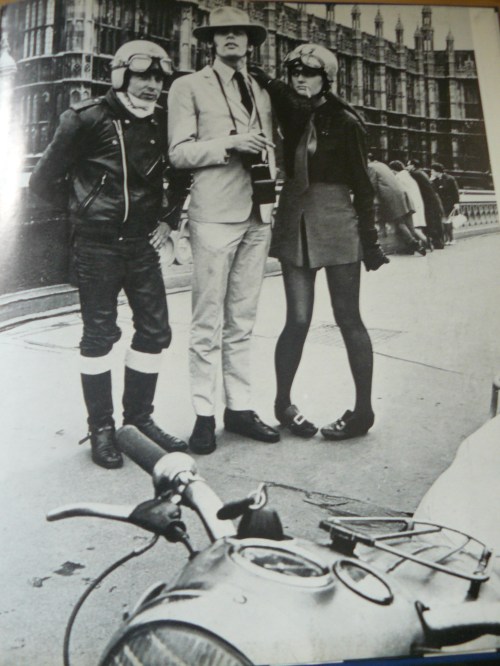

From Putney, the cyclists whizz through lovely Richmond – mind the deer! – before hitting the river at Twickenham, where they pass Eel Pie Island, nexus of London’s mid-1960s rock ‘n’ roll revolution. Numerous legendary bands played shows at the charismatic old dancehall on this tiny island in the Thames, including the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Rod Stewart. Among them was Tomorrow, one of England’s first psychedelic bands (featuring Steve Howe, later of prog-monsters Yes), whose 1967 single “My White Bicycle” was a big counterculture hit in 1966. This splendid slice of trippy frippery was written in homage to the pro-cycling scheme launch by Dutch anarchist collective Provo, who left 50 unlocked white bicycles all over their home city of Amsterdam in 1965, inviting the public to enjoy ‘free communal transport’ and rid themselves from the tyranny of the automobile. The Dutch police swiftly impounded the offending bikes, but the idea finally caught on in recent years in the form of the Paris bike-sharing scheme, Vélib. This idea was appropriated by London in 2010 and came to be christened Boris Bikes after London’s mayor, Boris Johnson, who inherited the scheme from his predecessor Ken Livingstone.

Boris Bikes can be hired by anybody with a chip and pin card at around 500 docking stations in central London. The bikes come without helmet or lock and are pretty hefty, but they are a fairly common sight in London. Although there is an ‘access fee’ (£5 for a week), the first 30-minutes of any ride are free, so smart users hop between docking stations and effectively ride around London for next to nothing. It’s all part of a belated attempt to make London a more-bike friendly city – four giant bike lanes, the blue-painted Cycle Superhighways, have alsobeen created in key commuter routes, with four more planned for 2013. If you want to borrow a Boris Bike to follow the 2012 road race route be careful, as there are few docking stations outside central London and costs soon mount if you go over the initial 30 minutes – while the fines for a late return are high.

From Twickenham, the race heads through Bushy Park and passes the Tudor palace of Hampton Court, before disappearing into the Surrey countryside. After a tour of the Surrey hills, the cyclists will then make the return journey, via Kingston, to the Mall. Sadly, then, there is no time to head to south-east London, where there are a couple of other prime London cycling landmarks. The first is the Herne Hill Velodrome, tucked behind suburban houses down a quiet street near Dulwich. This is the last stadia from the 1948 London Olympics still in use today. Built in 1891, the velodrome had all but closed during the Second World War but was brought out of retirement when London was awarded the 1948 games. It’s had a few scares since then – the gorgeous Victorian grandstand has been a no-go area for years – but was recently awarded £400,000 of Olympic legacy money and plans are afoot to construct a new grandstand, cafe and gym. The venue has played its part in nurturing the latest breed of British champion – Tour de France winner Bradley Wiggins raced here.

While Herne Hill lives on, the velodrome at Catford was demolished in the 1990s. Like the stadia at Putney and Herne Hill, this was built in the 1890s, when it attracted a very special guest. Absinthe-soaked dwarf artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec is usually associated with the Montmartre area of Paris, but in 1896 he turned up in the particularly drab suburb of Catford. Lautrec was a cycling fan, and had been asked by a company called Simpson to design a poster for their bike, which used a new type of chain. Lautrec was taken to the newly built Catford Velodrome to watch the bike in action during special races, set up by Simpson to advertise their product, and he produced a couple of images during his visit. The poster was one of the last he designed before his death in 1901, just as the Victorian bike craze was coming to an end.

Time Out went free this week. It wasn’t really a shock, the notion had been knocking around when I worked there, particularly when thelondonpaper and London Lite were stinking up the streets. The success of the free Evening Standard probably sealed the deal. The economics are unarguable: drop the cover price and circulation rises, allowing you to charge more for advertising. If you can simultaneously reduce costs – which they have been doing through regular redundancies – you may have a viable magazine once again. The danger, though, is that once the decision to go free has been made, there’s no going back…

Time Out went free this week. It wasn’t really a shock, the notion had been knocking around when I worked there, particularly when thelondonpaper and London Lite were stinking up the streets. The success of the free Evening Standard probably sealed the deal. The economics are unarguable: drop the cover price and circulation rises, allowing you to charge more for advertising. If you can simultaneously reduce costs – which they have been doing through regular redundancies – you may have a viable magazine once again. The danger, though, is that once the decision to go free has been made, there’s no going back…