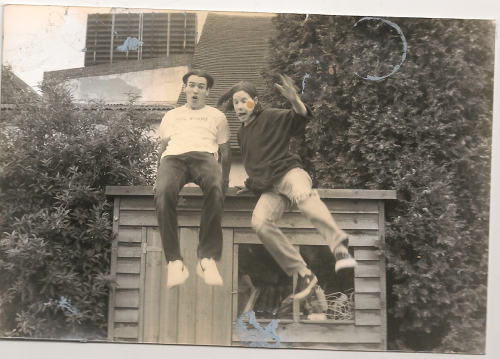

Here are me, Scott and Mike trying to be the Ramones.

We called ourselves the triumvirate and were inseparable. We were also insufferable poseurs.

We spent most Saturdays going up to London. The day usually started here.

The highlight of the train journey came after we passed Clapham Junction and trundled past the hulking mass of Battersea Power Station, which was apparently being turned into a theme park. This classic view of the power station from the railway line is soon to disappear as the building is surrounded by steel and glass boxes for the very rich.

Crossing the Thames, you could usually make out the floodlights of Craven Cottage and Stamford Bridge if you were quick. There are fewer finer sights in life then the glimpse of far-off floodlight. If all went to plan, we might be getting a closer view before the day was done.

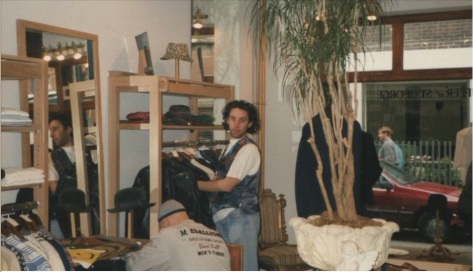

From Victoria, we headed for Covent Garden. Mike was a dresser. He could carry anything off. He still can. Mike had a dapper big brother, Pete, who read The Face and I-D, and so Mike always seemed to know where to go. His keen sense of style didn’t always go down well in the suburbs; when he wore a pair of Adidas shell tops to school, kids in Nike Air and Adidas Torsion laughed at his protestations that he was the trendy one. Still, I was convinced enough to buy a pair of suede Kickers on his say so, and nobody took the piss that much.

We usually went to a few shops on Floral Street and then Neal Street, maybe first visiting the Covent Garden General Store, which was full of entertaining tat.

We spent much of this part of the day traipsing after Michael into shops where saleswoman would assure him he looked the ‘dog’s bollocks’ as he pulled on another pair of check flares. If I was feeling bold I’d try on something in Red Or Dead or Duffer of St George on D’Arblay Street. On one treasured occasion, Mike’s brother Pete was so impressed by my red Riot + Lagos t-shirt from Duffer that he borrowed it for a party. This was probably the high point of my life as a style icon.

After watching Michael try on clothes, we’d go to Neal’s Yard, where we breezed past the weirdos in the skate shop on our way to the basement.

This was the Covent Garden branch of Rough Trade, a pokey den arranged around a metal spiral staircase, with walls covered in graffiti from bands that had played there. We loved it here. Music was one shared passion. Mike had got us into Sonic Youth, Pavement and Teenage Fanclub; Scott’s dad had a great selection of Van Morrison, Leonard Cohen, Jackson Browne and Neil Young. We all read the NME and Melody Maker and Select. This stuff mattered.

After a quick nose, we’d slip on to Shaftesbury Avenue and round to Cambridge Circus. There was a shop south of here on Litchfield Street that sold trendy Brazilian football shirts which we looked at but could never afford. Usually we headed north up Charing Cross Road to Sportspages.

Sportspages sold sports books, but we were only interested in the fanzines, which were scattered over the floor in untidy piles. Football was our other passion. I’d try and pick up the hard-to-find Cockney Rebel, a one-man Chelsea fanzine that combined football with an idiosyncratic take on pop and film culture. I went to Sportspages for years but never actually bought a book there.

Sportspages sold sports books, but we were only interested in the fanzines, which were scattered over the floor in untidy piles. Football was our other passion. I’d try and pick up the hard-to-find Cockney Rebel, a one-man Chelsea fanzine that combined football with an idiosyncratic take on pop and film culture. I went to Sportspages for years but never actually bought a book there.

After that, it was lunchtime.

We lived for bacon double cheeseburgers.

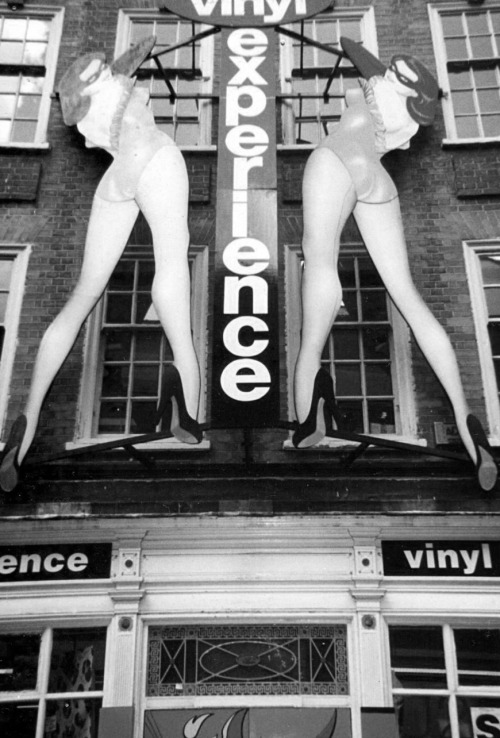

Then we’d head down Hanway Street, past the Blue Posts on the corner, to visit Vinyl Experience, a huge place over a couple of floors which was covered by this fine Beatles mural.

At some point earlier, it had this fine sign.

There were a couple of other record shops here – JBs was a decent one – and we’d often pop into Virgin on Oxford Street to check out the t-shirts.

From there, we strolled down across Oxford Street and cut through Soho down to Berwick Street, where three more record shops awaited – Selectadisc, Sister Ray and Reckless. Selectadisc was my favourite; although the staff were contemptuous, they were marginally friendlier than in Sister Ray and the choice was wider.

Sometimes we’d see our schoolfriend Martin, who worked the odd Saturday on a fruit and veg stall in Berwick Street market for his uncle. I was always slightly jealous of this; it seemed an impossibly cool, proper London job for suburbanites like us to have.

Football was next. Despite having visited so many shops, we spent more time browsing then buying so rarely had many bags. Most of our serious record shopping was done in Croydon at Beanos.

What game we went to depended on who was playing, how much money we had and whether I could persuade Scott (Wimbledon) and Mike (Celtic) to fork out to watch Chelsea. It usually boiled down to Arsenal in the Clock End, where we could still pay the kids fee, or Chelsea in the Shed. Occasionally we’d duck into the ground at half time, when the exit gates had opened.

If we didn’t fancy Chelsea or Arsenal, or they were away, we’d head over to QPR, Charlton, Millwall and Fulham. Nobody ever sold out.

After football, dinner.

If we had time, we’d pop into the sweet shop in the Trocedero.

And then maybe a gig: at the Marquee or Astoria.

Or more likely home via Victoria, and then out to the Ship or the Firkin in Croydon.

A week or so later, we’d do it all over again.

Many of these places no longer exist, and I’m not even that old. Or at least, I didn’t think I was.