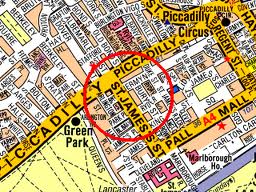

The story of Phyllis Pearsall and the A-Z is one of London’s most enduring and endearing myths. To take but one example, here’s the Design Museum‘s version of how, in 1935, Pearsall couldn’t find her way to a party in Belgravia so decided to make a completely new map of London, which she did by getting up at 5am each morning and walking every one of London’s 23,000 streets – a distance of 3,000 miles. The result was the A-Z, the first street atlas of London.

You’ll find this story everywhere, often repeated word for word, which is usually a sign something is up. Here it is on the BBC. Here it is in Time Out. Here it is on Wikipedia. And here’s some sap repeating it in an excerpt from a book on Amazon.

Peter Barber reckons it’s nonsense. And as the head of maps at the British Library, he should know.

‘The Phyllis Pearsall story is complete rubbish,’ Barber told me. ‘There is no evidence she did it and if she did do it, she didn’t need to.’

Barber maintains first of all that the first street-indexed map of London was made in 1623 by John Norden, but his reservations are not just academic. Pearsall’s father, Alexander Gross, had been a map-maker and produced map books of London that were almost identical to the A-Z in everything but name. They looked the same and used the same cartographical tricks. It’s Barber’s belief that Pearsall simply updated these maps to include the newly built areas of outer London and called the result the ‘A-Z’.

‘She was a great myth-maker,’ says Barber. ‘But English Heritage investigated the story and decided not to award her a blue plaque because it was not felt she’d done anything to deserve one [Pearsall does have a plaque, but it was awarded by Southwark]. It was marketing and it’s a very pervasive myth, she was a lovable character and people want to believe it.’

So did she really walk those streets or not? Here, Barber is hard to pin down. In writing he is equivocal, as the final comment here shows, but in conversation he makes his position pretty clear.

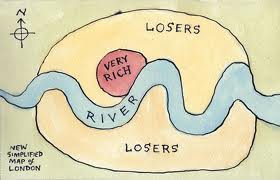

‘Pearsall was building on a body of information that had been around for years,’ he says. ‘What she may have done is be more thorough in mapping the new areas that cropped up between the wars, and there were two ways of doing this. You could either tramp the streets of outer suburbia for hours on end, or you could visit the local council office and ask for their plans. Which do you think she did?’