This is a piece I wrote for Eurostar about the conversion of Jimi Hendix’s Mayfair flat into London’s first historic house dedicated to a rock star (a small exhibition was held in the flat in 2010). Interestingly, even before the death of David Bowie, the museum’s curators were concerned the flat would be turned into a shrine by fans.

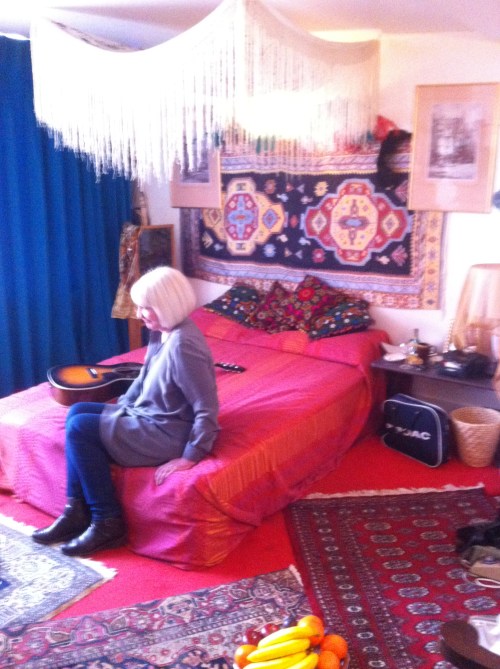

The museum is a strong addition to London’s cultural scene, filling a definite blank space. It begins with an informative timeline of Hendrix’s life focusing on his time in London, and then moves into this charming and evocative recreation of his tiny bedroom, which is both ostentatious yet surprisingly spartan.

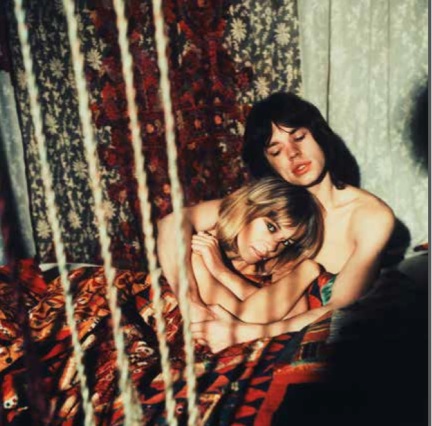

Hendrix’s reconstructed bedroom, with former girlfriend Kathy Etchingham

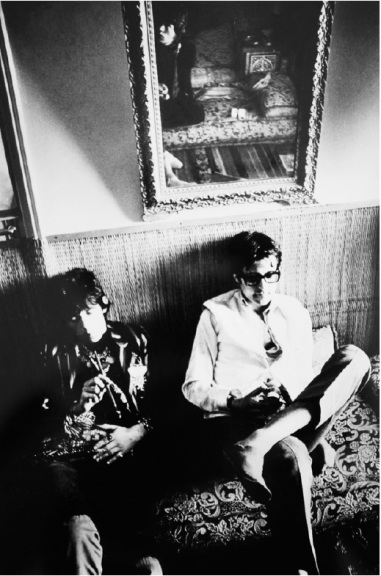

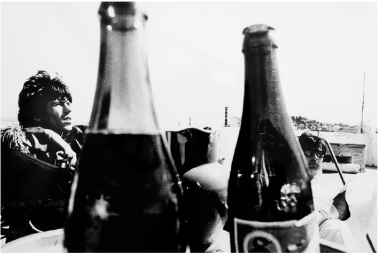

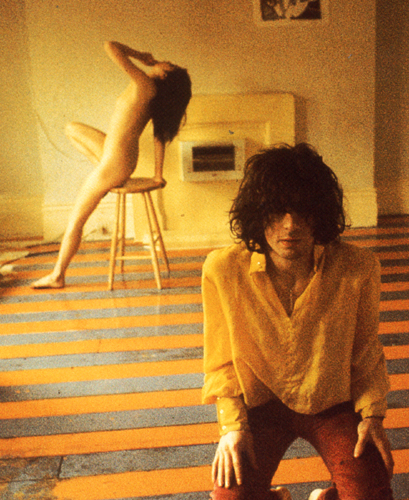

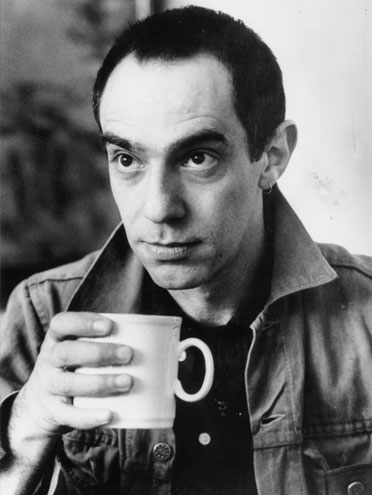

When Barrie Wentzell photographed Jimi Hendrix at the rock star’s London flat in 1968, neither of them imagined that the colourful bedroom would one day be transformed into a museum. “I photographed him for Melody Maker,” says Wentzell. “It seemed so small when I went back recently. He’d have found it hilarious that it’s being turned into a museum.” Hendrix moved into 23 Brook Street in January 1968 with his girlfriend Kathy Etchingham, using it as a base to explore London as well as a space to conduct interviews and hang out with fellow musicians – George Harrison was one of those who stayed overnight on a camp bed. Since 2001, the flat was used as offices by the Handel House Museum who are located at the 18th-century composer’s old home next door at No 25. The entire space is now being renamed Hendrix & Handel In London, and Hendrix’s flat will open to the public in February 2016.

Hendrix arrived in London in September 1966 and began playing shows on his first night, immediately attracting the attention of a London music establishment who had seen or heard nothing like him. Incendiary, transformative early gigs in tiny West End clubs were witnessed by the likes of Eric Clapton, Pete Townshend and The Beatles. “All those guys, they played the blues but Hendrix had taken it to a different level,” says Wentzell. “He told me once, ‘Sometimes I play the guitar and sometimes the guitar plays me’. But he was very humble and soft-spoken, he kind of under-rated himself. He would talk about how great Clapton was and Clapton said the same about him. They had real love for each other.”

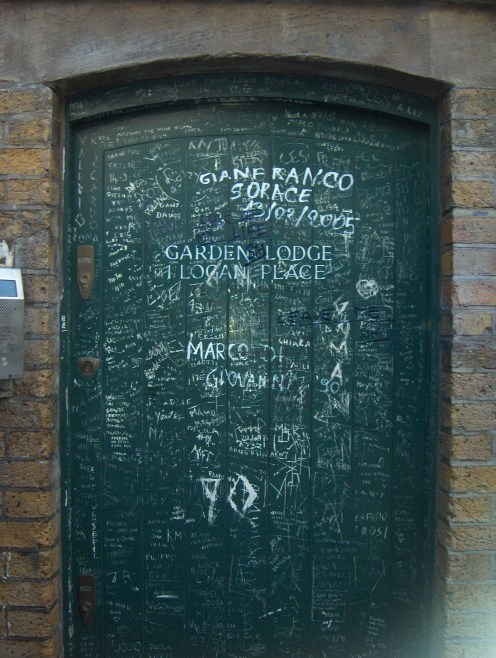

London boasted a powerful music scene packed into a small corner of the West End, and word about Hendrix soon spread. He became a star and as a result, he loved the city. Although he’d met Etchingham on his first day in London, he spent much of those early months moving between flats and hotels. “He moved around an awful lot and had lots of girlfriends who all thought they were the one,” recalls journalist Chris Welch, who interviewed Hendrix several times. Etchingham and Hendrix eventually moved in together, paying £30 a week for the pokey one-bed Mayfair apartment above a restaurant called Mr Love. Hendrix called it “the first real home of my own” and helped select ostentatious decorations of bright fabrics, peacock feathers, bric-a-brac and a rubber rat. The bedroom, which is where most of the entertaining took place, is being recreated for the museum after curators identified and tracked down around 70 items of furniture and fittings. Other exhibits include clothes, records and guitars as well as a timeline exploring Hendrix’ pivotal London months.

Although Hendrix spent his time in Brook Street enjoying some level of domesticity – he played Risk and watched Coronation Street – he also threw himself into the world of Swinging London, which was right on his doorstep. Promotors, agents, publicists, music papers, clubs, guitar shops, studios and fashion boutiques were all based in Mayfair and Soho. “He was in the best place to be,” says Welch. “Bands from all over the world converged on London and it was still the hippie era so if you were going to be accepted for being unusual anywhere it was the West End. He was adopted by Londoners very quickly.” Wentzell agrees. “There was a lot of love for Jimi,” he says. “He was only around for four years and he changed the world, he really did.”

Hendrix, who died in London in September 1970, always loved the flat’s connection to Handel – indeed, he believed he was living in Handel’s old home as Handel’s blue plaque was on the wall separating the two properties. “I remember him saying that he got this vibe of music from Handel and we joked about how he’d like to have jammed with him,” says Wentzell. “I guess now he is.”

Handel & Hendrix In London, 23-25 Brook Street. Opens on 10 February 2016.